Worldwide, the pressure from climate-induced sea level rise (SLR) on urbanized coastlines is growing. The ‘very likely’ range SLR scenarios (<3 m in 2200, 90% confidence interval) constitute significant biophysical and socioeconomic adaptation challenges. Meanwhile, high-end SLR scenarios (3–8 m in 2200) from icecap instabilities, pose even greater threats. Historically, wealthy urbanized coasts have typically adapted by building increasingly-large flood defense systems. This ‘protect’ strategy is projected to be robustly cost-effective for 21st century SLR, making it likely that other affluent coasts will follow suit.

Transformational adaptations like ‘accommodating’ to SLR by (partly) retreating from high-risk areas or, conversely, ‘advancing’ the first line of flood defense seawards are gradually entering policy arenas. In the Netherlands, a wealthy, urbanized delta with a strong tradition in flood defense systems, high SLR scenarios have sparked a heated debate: Should we follow the historical path of building ever-higher dikes to protect current and continued investments behind these dikes, or should we opt for transformational alternatives? Ultimately, many global deltas will face a similar question. Highly urbanized economies that are locked-in along the coast will be exposed to unprecedented growing flood hazard. An example is the USA, where increasing flood risk leads to an alarming decrease in flood insurance coverage and affordability. The Dutch debate is therefore informative to deltas worldwide.

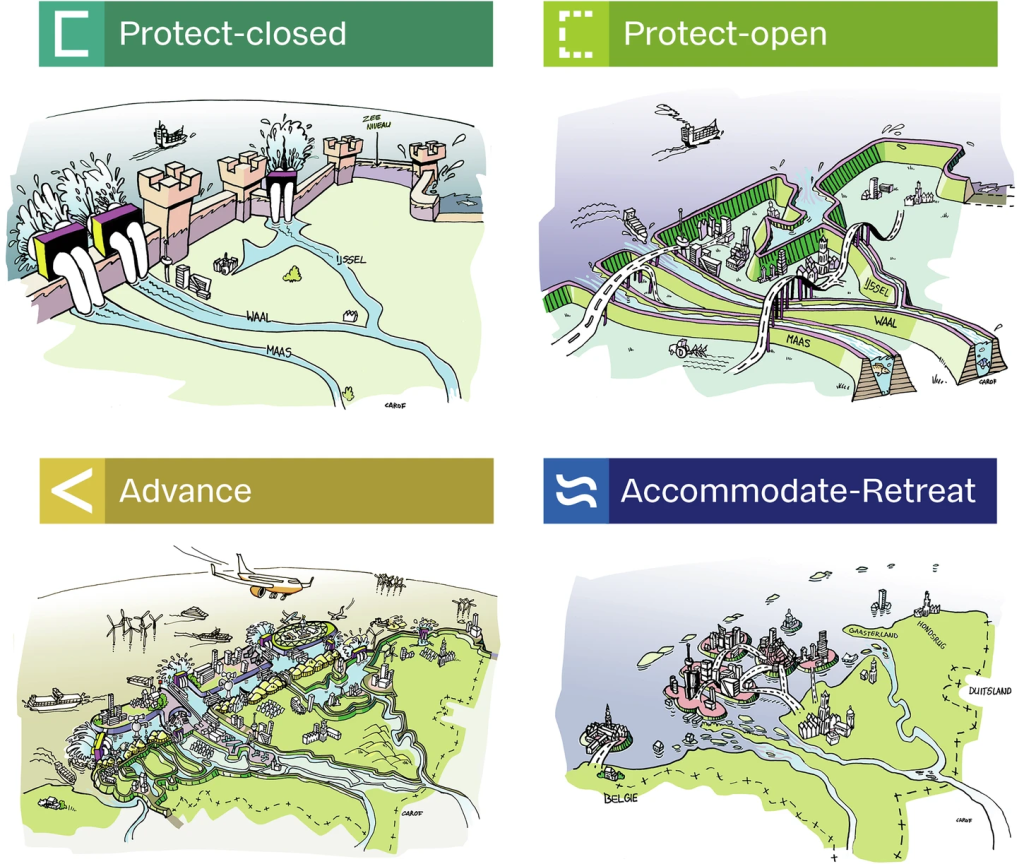

The Dutch SLR debate polarized around two extreme strategies: Protect vs Accommodate-Retreat. Protect aims to ‘hold-the-line’ through raising flood defenses and other technical solutions. Conversely, Accommodate-Retreat advocates nature-based solutions and ‘living-with-water’ instead of fighting it. While both strategies aim to protect economic development, neither sufficiently considers how economies are bound to respond, for example via mechanisms like restructuring of economic activities, repricing, and reinvestment. Cities are assumed to simply follow the adaptation strategy: either remain concentrated in their current locations (Protect), or shift to higher grounds (Accommodate-Retreat). However, history worked differently: flood protection followed economic development, in turn boosting the growth of population and capital in hazard-prone areas. Coastal adaptation debates should consider the economy as a dynamic rather than a static factor.

Figure: Four archetypical strategies for dealing with SLR in The Netherlands

(Image by Carof beeldleveranciers for Deltares)

The adaptation dialog should be extended with a perspective in which economic and financial mechanisms are thoroughly integrated, acknowledged, and understood. Finance and economics entail forces that will follow and steer; they can influence and be influenced by SLR and adaptation policies. In this paper, the term ‘economics’ refers to the real economic system (households, firms, governments) with its flows of production, consumption and distribution of all goods and services. ‘Finance’ refers to the financial system (financial markets, investments, banking, insurance) and its monetary flows. We not only argue that financial and economic mechanisms are important, but also explore what the important mechanisms are.

This study provides an overview of the economic and financial mechanisms triggered by sea level rise adaptation strategies, supported by stakeholder insights. A research agenda for urbanized coasts worldwide is also provided.

How an economic and financial perspective could guide transformational adaptation to sea level rise

by Kees C. H. van Ginkel, Bart Rijken, Marco Hoogvliet, Wesley van Veggel, W. J. Wouter Botzen & Tatiana Filatova

npj Clim. Action 4, 89 (2025).