The ACCREU Adaptation Decision Type workshop on “Strategies and barriers to climate change adaptation for food-water-biodiversity for the Human-Nature systems in Europe” aimed to generalise the lessons learned from the ACCREU case studies and identify practical adaptation solutions that can be taken up by other stakeholders. The workshop took place as part of the ACCREU project activities, on the 13th of March 2025 and targeted adaptation practitioners.

The workshop was the first in a series of ACCREU workshops, each focusing on specific adaptation decision types, and addressed the nexus between water management and food production on the one hand, and biodiversity conservation under the threat of sea level rise on the other. More than 20 stakeholders from adaptation practice and science participated in this on-line meeting.

Stakeholders participating in the workshop came from two ACCREU case study sites focusing on water management, the Ebro river basin in Spain and the Thaya river basin in the Czech Republic. Stakeholders focusing on biodiversity came from the Venetian case study OASI Alberoni, a small, protected area with a beach and coastal dunes belonging to the city of Venice.

Adaptation challenges in the two river basins arise from declining water availability, which barely satisfies the increasing water demand within the basin, coming from households, industry, energy production, agriculture and biodiversity. Increased water demand is expected from agriculture to mitigate the effects of climate change. The challenges of climate adaptation in the protected area are linked to sea level rise and changes in patterns of extreme events, overlapping with anthropogenic pressures and pressures from invasive species, all of which threaten dune habitats and functionality.

The solutions discussed in two breakout groups related to financial instruments and governance solutions respectively.

Two good examples were presented to the audience:

A model for creating fiscal incentives for local authorities to conserve biodiversity showed one way of generating financial resources for local communities to conserve habitats. The model, applied in Portugal, provides for an increase in fiscal transfers (national to local) to local authorities with a high proportion of protected areas on their territory.

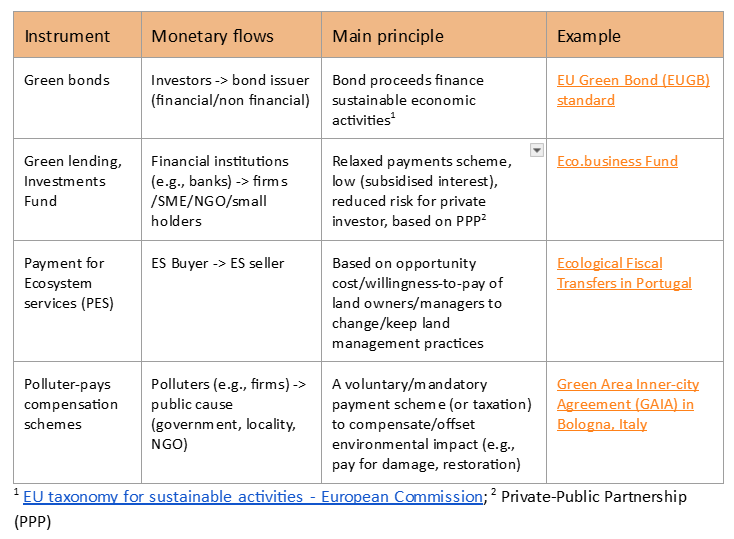

Other examples of financial instruments were introduced to the workshop participants, including the recent EU Green Bond standard, green lendings, and voluntary Public-Private Partnership (PPP). The table below provides additional details on the different instruments.

A governance model in southern Sweden illustrates how benefits and costs of river naturalisation in an agricultural area can be shared. Farmers in the area transferred rights of use for parts of their land to a farmers’ association, which managed the river restoration, creating new wetlands and multifunctional reservoirs for irrigation. The transformation of the watershed, financed with public funds, increased farmers’ resilience to floods and droughts.

As a third example, workshop participants presented the island of Juist, a small dune island in the German Wadden Sea, where a well-conserved natural environment works effectively as a tourist attraction.

Concerning the OASIS Alberoni nature reserve, stakeholders raised concerns that protecting habitats from human activities is a more urgent priority than supporting their adaptation to the impacts of climate change. Stakeholders report that lack of support is a major problem, with the local authority favouring tourism and property development over conservation. They denounce a general lack of awareness of the need to conserve biodiversity, both on the part of the authorities and among visitors to the area. This lack of awareness, combined with the high pressure of property development and tourism, makes consultation difficult and access restrictions to the beach area necessary to protect species and habitats. Visitors are attracted by the beach and enter the protected area regardless of the protected status and the rules associated with it.

Solutions discussed by stakeholders range from raising awareness and restricting access to fragile ecosystems such as dunes, to shifting the visitor profile towards ecotourism. About the local authority and local residents, the function of a well-preserved dune system as a protective measure against storm surges could be used as an argument, for example, to prevent the local authority from granting further concessions for tourist facilities (restaurants, bars) within the dune area and to support dune restoration, and to get farmers to accept the expansion of forests and the creation of wetlands to increase water availability and reduce flood risk. Such benefits would need to be well communicated to decision-makers and citizens, considering general preferences for short-term benefits and income generation. More generally, despite the long-term benefits that ecosystem services can provide to economic activities by increasing resilience, compensation would be needed to shift economic activities such as agriculture, forestry and tourism towards conservation activities. In this context, the Payment for Ecosystem Service (PES) concept was discussed as a potential scheme to estimate and communicate cost avoidance associated with climate change impacts and extreme events. The direct involvement of key stakeholders in the management of protected areas and compensation for income losses caused by conservation measures can help raise awareness of the benefits of conservation and contribute to a slow process of mental change.

EU Taxonomy https://finance.ec.europa.eu/sustainable-finance/tools-and-standards/eu-taxonomy-sustainable-activities_en